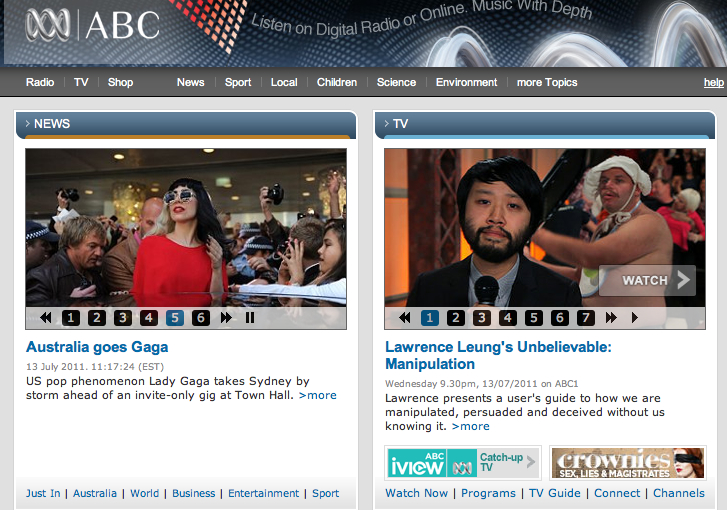

Persuading people is an art. Anybody who has studied argument-writing knows this. And it is what amused me about logging into the ABC website and seeing this:

If you’re like me, and you don’t consume popular television at all (yeah yeah, oh the gasp, shock blah blah), then you could be forgiven for thinking – not knowing any better – that Leung’s Unbelievable is a serious show. Especially with that blurb beneath the title:

Lawrence presents a user’s guide to how we are manipulated, persuaded and deceived without us knowing it.

You will likely be drawn into this conclusion by the fact that it is the first thing on the ABC homepage, alongside the broadcaster’s top news stories. While this picture (above) depicts the popular puppet Gaga, the other headlines included things like carbon rorts, consumer confidence reports, Murdoch’s hacking allegations, and so on. Furthermore, given that the ABC occsasionally does post some entertaining and informative material – Gruen Transfer, anybody? – all the arrows point in the same direction.

The wrong direction. Leung’s show is not serious at all, and this episode about manipulation is what you would expect from white trash pulp: tarot readers, psychics, debunking the notion of alien life, and so on.

The one thing it did right was push me to write about the art of persuasion. And this just after I was moaning on Twitter the other day about how I never get blown away by teenagers’ ability to think critically any more. We had to, when I went to school, there were whole assignments based on the skill. How to critically analyse the media; how to critically analyse symbolism; and other such postmodern bits and bobs.

Then I hit uni and learned what critical thinking is really about, a million years ago in first year. I am amazed I remember any of it, because it was tough going when I was 19.

Let’s look at rhetoric

Regarding persuasion, the man with whom the buck stops is Aristotle.

Ever hear about our brothers ethos, logos, and pathos? No? Sit tight.

Originally pedalled as the three pillars of public speaking, these elements of Aristotle’s rhetoric tell us not only how to persuade people, but are also the tools that help us to determine the hows and whys of our own manipulation. People talk about using the three pillars in their fiction writing, in their public speaking, in journalism (surprise surprise), in essay writing… in just about any area of writing you can imagine. Rhetoric is, after all, the art of persuasion. And, as Wikipedia will also tell you, Aristotle’s Rhetoric is considered the most important work on this topic that you can find.

As an interesting aside, I’ll give you this to mull over:

…. Socrates, Plato and Aristotle saw rhetoric and poetry as tools that were too often used to manipulate others by trading on emotion and neglecting facts. They particularly accused the sophists, including Gorgias and Isocrates, of this. Plato, in particular, laid the blame for the arrest and death of Socrates at the feet of sophistical rhetoric. In stark contrast to the emotional rhetoric and poetry of the sophists was a rhetoric grounded in philosophy and the pursuit of knowledge or enlightenment. One of the most important contributions of Aristotle’s approach was that he identified rhetoric as one of the three key elements of philosophy, along with logic and dialectic. Indeed, the first line of the Rhetoric is “Rhetoric is the counterpoint of Dialectic.” Logic, to Aristotle, is the branch of philosophy concerned with reasoning to reach scientific certainty while dialectic and rhetoric are concerned with probability and thus are the branches of philosophy best suited to human affairs. Dialectic is a tool for philosophical debate; it is a means for skilled audiences to test probable knowledge in order to learn. Rhetoric is a tool for practical debate; it is a means for persuading a general audience using probable knowledge to resolve practical issues. Dialectic and rhetoric together create a partnership for a system of persuasion based on knowledge instead of manipulation of emotion.

Out of all of that fun stuff, we find that Rhetoric was originally one branch of the discipline of philosophy, and that it was a ‘means for persuading a general audience using probable knowledge to resolve practical issues’.

Aristotle defined rhetoric as the ability to see the available means of persuasion.

I’m kind of going through these backwards, but following is a bit of a description of the three tools, ethos, logos, pathos.

Logos is reasoned argument, or ‘argument from reason’. It is reasoned discourse, the ability to speak with clarity, logic, and reasonableness. It is what makes you appear prepared, and knowledgeable. Logos may be data, facts, figures, or the construing of such. Whatever it is that logically makes you look like you know what you are saying.

Pathos is the appeal to your audience’s emotions; or, rather, to its sympathies and its imagination(s). Pathos is more refined that merely drawing an emotive response from your audience. It is the ability to tie that emotive response to your audience’s empathies, to engage them well enough to imagine themselves (or someone close to them) in a particular situation. By tying the pathos to your audience – each audience member in turn – your work has a far greater persuasive appeal.

Ethos is the most important of the three, which is why it is characteristically listed prior to the others. Ethos is an appeal to the honesty or authority of the speaker (or writer, or subject). While the persuader can provide a way into this, it is truly the audience that determines ethos. Drawing on ethos can be done in multiple ways:

- By being a notable figure in the field in question, such as a college professor or an executive of a company whose business is that of the subject.

- By having a vested interest in a matter, such as the person being related to the subject in question.

- By using impressive logos that shows to the audience that the speaker is knowledgeable on the topic.

- By appealing to a person’s ethics or character.

Apply rhetoric to your writing

If you’re a fiction writer, then right about now you are wondering how the bloody hell this applies to you. It’s actually not that difficult.

If you are a character writer, then the way that you speak with authority and clarity about your character makes you know what you are talking about (logos).

If you know what you are doing, then your audience will identify with your character, either positively or negatively, and will be more willing to suspend their disbelief and follow your story (pathos).

And if you do the other two correctly, your apparent honesty and authority will appeal to your audience, making you as the writer disappear into the background – thus enabling greater engagement with your character (ethos).

See? Simple. It’s merely putting strange words on what you already do.

When most people hear the word rhetoric spoken aloud, they do not think of its original meaning, of persuasion. What they think of is its second meaning: pompous, bombastic writing. Which, let’s be honest, if the person peddling persuasion does it not with artfulness but instead with a bag of shit, is what you get.

Use rhetoric to deconstruct the media

Knowing how to create something also teaches you how to deconstruct it. It is occasionally more tricky, it may involve a little more work of your grey matter, but you have the skill to do it. Once you know the three elements of persuasion, you can work out whether or not you are being manipulated (persuaded) into taking a particular point of view.

If you’re reading news articles, then you also have to look at lexical semantics (or the meanings of words and word relations) – and pay particular attention to timbre or the tone of the language used. By adding this fourth element, which you would naturally come to via pathos, then you’re well armed to tackle the onslaught of information thrown at you by the media. And by any friends, workmates, or family who are already persuaded, and are thus regurgitating what they’ve seen or read.

Let’s try this out

This screen-grab is from the ABC’s article ACCC Flying Squad to Combat Carbon Rorts. I chose it on purpose, because of its title. 😛 Have a read:

Firstly, let’s go with the title. What’s it bring to mind? War planes? Images of tough, trained professionals? Probably agile ones?

Moving into the body of the article, this image is reinforced by the use of language such as track down, punish, rort, false and misleading, force, laws… and so on. Already you’re feeling your pathos-strings pulled, aren’t you? It’s appealing to your sensibilities that companies who evade the law need to be dealt with, because at heart you’re an honest person. If you were being dishonest at such a level, you would expect to be dealt with… You see? Not only are your emotions engaged, but so is your imagination. Your sympathies are already siding with whatever argument this writer is proposing, and you’re not even thinking about it.

The logos in this article is in its structure, as it is in most persuasive texts. It has an introduction, it states some facts at the beginning, and it rolls on through other apparent facts that feed into the basic drive of the argument. When you get to the second and third paragraphs, however, do me a favour and pause. Now explain to me how misleading advertising and consumer laws are related to companies who flaunt carbon tax laws? You’re struggling, right? It seems ok, false and misleading claims appears to lead naturally into misleading advertising. The consumer laws appear to be related to carbon taxes. But, if we’re honest, it’s a really tenuous link.

This, then, is where the fact babble of logos can be used against an audience, to create a situation where the ‘facts’ persuade. But they needn’t be correct, or properly related, so long as it creates this effect in the audience’s mind.

There are a couple of reasons why you aren’t questioning the authority of the writer (ethos). The first is tone of the work. It is suitably journalistic, stitled, correct. Its short sentences are authoritative, and leave little room for questioning. But in the body of the piece it also draws on experts: it name-drops the ACCC, a body that all Australians aspire to complain to when companies don’t do their thing as they ought to. It pulls out a previous case, though tenuously related, against Optus (everybody has a beef against a telco, right?). It draws on some significant names: the deputy chair of the ACCC itself, and provision of quotes; and the Treasurer, Wayne Swan, and provision of quotes. So why would you question the authority of this work, or its honestly? It quoted high-up people, from significant organisations.

But the important thing is to work out the goal of this piece. Its goal is to get you to agree with the notion that the carbon tax is a good idea. And the best way to do that is to pitch you against the faceless ‘large corporations’ who so often appear to screw us blind.

Has it told you anything useful? Anything new? Has it given you any information to enable you to make an informed decision on your own? Even though this is only a snippet, the answer (based on what is provided) is a resounding no. All it tells you is what the potential fines are, and what the potential taskforce will be that will enable distribution of those finds: a group of 20 people.

Everything else is a tool of the rhetoric, designed to help you think in a particular way.

I hope you enjoyed this little excursion into the art of persuasion. Please drop a comment and let me know what you think!

But I haven’t watched Leung’s show. I need to watch it. I shouldn’t ramble off opinions without watching the show first.

Well to be fair, I watched the shorts myself. It was enough 😛

I haven’t watched Leung’s show, but generally when a stand up changes their format, it is such a big leap from the stand up circuit to a broadcast quality show that the funny gets lost in translation. With the exception of Hannah Gadsby, who did a two part Artscape on the story of the NGV. It was hysterical as well as an articulate and informative show (if you give a shit about art in the slightest at least) and I cannot remember the last time I watched something that interesting as well as belly-laugh funny. Leung is a talented stand-up, for sure. As well as a cute and engaging personality, but his show seemingly lacks insight for comedic or informative results. Gadsby had the advantage of having an investment in the subject matter (I think she may have been an art historian before her comedy career took off) and an opportunity to show case that knowledge and passion using her skills as a successful and skilled comedian.

Finding examples of well thought out shows that are executed with timing and performances that bring the laughs are few and far between (can of worms springs to mind). If the ABC had the production power of the networks but retained it’s integrity, a show put together by a talented comic like Leung would probably be more than a cobbled bit of comedy pretending to be … what is it even trying to be? Satire? If Channel 10 retained it’s production buying power but somehow was infused with integrity (more normally associated with the ABC) then when Andrew Denton got behind a show like Can of Worms, trying to popularise important issues would be more palatable than what they ended up with; a cheesy game show with a lack lustre host and a fat blonde side kick pretending to be informed on the issues because she does voice overs on some graphically impressive polling results. (hate meshel laurie – once was the Whore Whisperer, she makes me want to vomit. Why are funny women in Australia only allowed to be fat or alcoholic. Or gay. If you’re anything but, shut up and look pretty) Le sigh.

If you could somehow control the wizards behind the curtains and bring all of the right elements together, your analysis of how to engage an audience would be the mission statement of production companies far and wide. A best practice goal of producers, directors and writers, but let’s face it, if media was intended to work to the collective good, how would the John Hartigans of this world afford their harbour views?

Persuasive writing is most definitely an art and I can remember persuasive writing essays and critical thinking exercises from school. I have no idea what the curriculum is like now but it would be a tragedy if kids were missing this! A persuasive essay for English in years 10, 11 and 12 was the most exciting piece of assessed work I could be tasked with. I loved them. I once charged a girl in my year a 35 deck of escort reds to write one for her (luckily, when someone who never does their work hands in something I would have gotten a C on, they get an A. Injustice, but cigarettes aren’t cheap! I’ve always been one to trade on my portable commodities!)

Your blog is one of the best I read Biodagar, why are you working where you work? Your brain needs a bigger paddock to run around in!

The best thing is, I am now ashamed of the shoddiness of the writing in my blog and am determined to step my game up.

Seriously though, can I borrow some of this and dumb it down for my writing workshops? Not to insult anyone who would attend them, just heavy language for people, some of whom have no formal education.

Thanks love. I love your long rambling replies! And cheers for the compliments, makes me blush. >< Yes you can take this for a writing workshop. I'd even present it for you (or help you) if you wanted 😉 it is the basis of any article writing, really, that's for sure. Ah the age-old why do I work where I do? Nobody wants to give talent in this town a job that suits. I just don't fit the box! So... Reception it is. What a waste lol