What happens when young critics receive – or do not receive – publicity materials? And are they necessary? Let’s find out.

If you’ve ever worked as a journalist in the music industry, you would know exactly what I’m talking about when I refer to a one-sheet. If you don’t know what a one-sheet is, here’s a definition taken from this wiki page:

In music publicity and distribution, a one-sheet is exactly what the name implies: One sheet of paper, on which information is provided about the musician and/or a specific release which is being distributed. One-sheets often accompany a record or CD when it is being shipped to radio stations and music publications (i.e., magazines, Web-based forums, etc.) A one-sheet is sometimes also referred to as a press sheet or a promo sheet.

Other industries have one-sheets, too; but often they are simply sales pitches. In the music industry, this notion of ‘selling’ on a one-sheet is a lot less obvious, because of its tie-in with publicity.

A publicist once told me that when he worked for a major label there was often tension between marketing and publicity. Marketers have a penchant for saying to publicists: “What I try to sell, you give away!”.

The notion that publicity is not selling, or is perhaps ‘soft’ selling, is bit of a white lie. The intention of publicists’ work is to spread information about their bands and their bands’ activities. What you will find, though, is that it is actually a sales pitch: the materials exist to help people provide good reviews and good press; to enable greater news reporting, thereby increasing the visibility of a label’s “product” (which is the band itself).

There is a second step to this sale, too. Through heightened visibility, and more reviews, you potentially generate higher sales. Through increased news reporting, you also gain heightened visibility in regards to tour dates: thereby potentially selling more tickets and more merchandise.

At its core, publicity is sales. It is unpaid advertising. It is marketing through generosity and useful, newsworthy information. And for critics who are reviewing materials, it often provides information about a release that they may not otherwise receive, thereby increasing a writer’s understanding of what he or she is listening to. The more information you have, the better able you are to make an informed judgement; therefore your review will be more critical.

At least, this is the understanding. But for those writers who are unschooled in rhetoric, a thinly veiled sales pitch in a one-sheet can exert undue influence on a review.

It is crucial for journalists and critics to realise that publicity materials are sales pitches, in whatever form they may take. Having written publicity material for bands myself, I know this intimately. Writing text for publicity purposes is exactly the same as writing text for sales, advertising, or press release purposes. It is merely framed differently.

Let’s look at a one-sheet, and break it down a bit

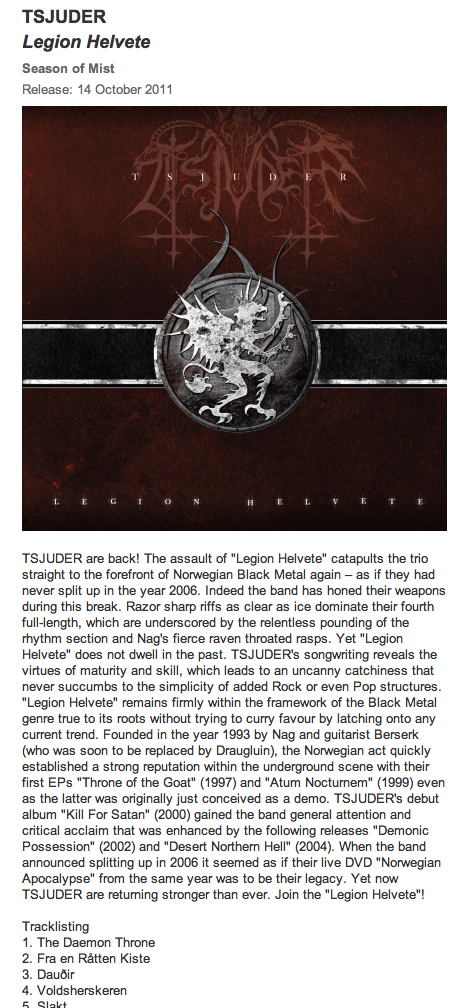

It’s a good time, at this point, to throw in an example. Below is an example of a one-sheet from Season of Mist. Their one-sheets are always pretty good. They (a) give me information about the release, plus artwork, and the band and the band’s history; (b) give me a track-listing, and never fail to; and (c) give me the current lineup of the band – which in this example you can’t see.

Let’s have a look:

Now, if you have read my previous post on rhetoric and persuasion, and how to break down copy, you would be able to recognise the sales pitch in this pretty easily. If you haven’t read that post yet and you can’t see the persuasion/sales in it, have a look at some key words: assault, forefront, the notion of the band being as fabulous as they were back before they split up, but they are better, maturity, catchiness, simplicity, clear, sharp riffs… nearly the whole first part of the text, in fact, has an overwhelmingly dominating positive spin.

You can’t argue that this is a bad thing, because everybody has to sell their products – in this day and age, more than ever. What you can argue is that one can be unduly influenced by this material before having heard the album. Don’t forget that this one-sheet accompanies the release.

Back before the advent of online promo systems like Haulix, one-sheets would come folded in half, slipped into the front of a CD case; or sometimes hanging out of the top of a paper CD sleeve. Exactly like in the picture at the top. You read them, went ‘oh yeah’. You only kept them if you found them valuable for some reason, like it contained a tracklisting that the CD didn’t come with.

Now, however, things are different. You see this writing every time you log in to listen to those tracks on your Haulix account; or if you have to download it a couple of times because your system is like mine and screws up all over the place.

The key issue is that you and your young critics are being pounded with positive spin.

Many unschooled reviewers (separate from critics; critics usually know what they’re doing) drink in the one-sheet, like they drink in information about their favourite bands. Then they listen to the release, with the happy expectation that it will meet the levels insisted on by the one-sheet. Huge numbers cannot discern the difference between what they hear and what they’ve been told to hear, so you tend to get positive reviews from these cats.

Whether the album deserves it or not.

Not getting a one-sheet can sometimes be a godsend.

It is really nice to get releases without one-sheets occasionally, because you have to listen to the material and work really hard to decide on what you think is an appropriate response. It’s not so much of a terrible thing, given there is the internet to assist with artwork, track listings, band compositions, and so on.

And, to be perfectly honest, the most useful material to a critic includes:

- lyrics

- art

- visual artist

- studio where recorded

- who the producer(s) was/were

- track listing

- band composition

- guest appearances

- … and so on.

I would rather be able to give kudos (or the reverse) to specific people if I feel it is warranted: to artists who produce cover art and liner art; to producers who create great or shit sounds and mixes; to good (or otherwise) performances by guests. I would rather be able to come to my own understanding of an album through an entire package of art, lyrics, and music, and be able to talk to it knowledgeably, than to get some spin about where the band has come from. Because, honestly, who cares.

It is the art that is important. And ‘art’ is defined as the entire package when we talk about music. You cannot just take the music, because bands always make decisions on artwork and layout; and they often collaborate on lyrics, even when there is a primary lyricist. The lyrics are part and parcel of the music.

If you have a concept album, then nobody can argue that any part of it is unnecessary. Done right, the concept takes in visuals, words, music, and sometimes even videos.

Actively think whether to give your writers publicity material, if you have the choice.

It is sometimes necessary to provide budding critics with just the music and force them to hone their skills without the input of a publicist’s carefully crafted text. It is vital to do it for critics whom one is mentoring, or whom one believes has a chance of being a critic or journalist of repute one day. It helps them, and it helps you to publish quality content.

Withholding one-sheets can sometimes be damaging, though. If you intend for your writer not only to review the album but to interview the band afterwards, he or she will require the one-sheet. Why? Because usually the one-sheets provide valuable information – including, sometimes, quotes – that other sources may not be able to provide.

A good journalist will scout existing press for interviews with a band he or she is set to interview, too, to gain information and to prevent mindless repetition of questions on the same album cycle; but sometimes the one-sheets will give you that little bit extra. There’s no point asking stupid questions about (taking our example above) ‘the album’ Atum Nocturnem when it was an EP, for starters, and conceived as a demo as well.

If your writer does not know a band very well, the label’s publicist can sometimes save them from looking like an idiot. I don’t need to say that idiotic writers make publications look idiotic.

Whether you choose to use publicity materials you are provided (I like to refer to it as the Force, simply because if you don’t watch out, you’ll drown in them!) is largely a matter of personal discretion. Whether you train your writers to realise that publicity materials are sales materials is also up to you. It is a good idea. I had some writers at various points whom I wish I had educated on the matter; but hindsight is always 20/20.

Publicity materials definitely have a place in a music critic’s life. The key is working out how to use them to your advantage – rather than relying on them wholesale. Because if you do that, then you run into the issues I wrote about here: of content versus quality.

This post is an early draft essay in a series of critical examinations of music criticism, rock journalism, and the publishing of such. The project is being co-written by Tom Valcanis who was one of my best music journos, and is a blogger and writer/theorist of critical rock journalism. Click here to read his first post, Push-button Professionalism: the origin and evolution of the role of professional music critics.

1 thought on “Using the Force… or not. The place of publicity in contemporary music criticism”