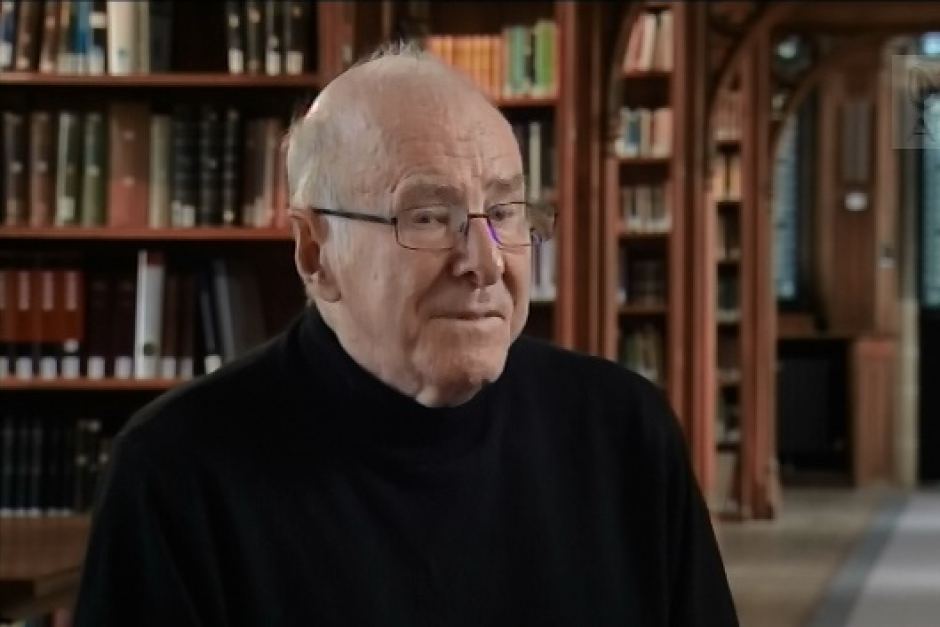

Clive James is a man of significant influence in my life; and yet it was only recently that I realised that the greatest gift he’s ever given us is his time.

In a moment of bizarre time-warping, an interview that I had thought was recent, because of its sharing on a streaming platform (ABC iView), had deceived me. Here was I thinking that Kerry O’Brien’s interview with Clive James was completed sometime in the last twelve months; when in fact it is almost three years old.

Duped by the internet. What can I say.

In any case, Kerry O’Brien’s interview with Clive James was handled with a sensitivity that only fans of James’s work could achieve. In a written round-up (that honestly did very little to shine a light on the interview), the ABC claimed that, “O’Brien says it is one of the most satisfying interviews of his career”. This was clear, even in the small pieces of film with O’Brien’s head in them. He was trying not to smile like a fanboy taken over by his delight at being in the room with one of his heroes, and spoke and questioned the famous critic and poet with the deference of a lifetime of respect, passing lightly over deeply personal subjects that could have turned the interview into something far less valuable. Watching Kerry O’Brien handle the touching, difficult subjects is great education for all of us; perhaps more so for those of us for whom interviews are not strange things.

For me personally, the insight into Clive James’s life was particularly rich. I wept over his grief. I smiled girlishly alongside O’Brien’s boyish grin. I was the proverbial sponge to the waters of wisdom that emerged from the discourse. And the influence that this author has spread into my life, from the very first moment I read his Unreliable Memoirs, what seems like a million years ago, gained a new light.

While Clive James stands in his stead as perhaps one of the most influential writers in my life, I say it having barely scratched the surface of his works. For example, I was unaware that he had translated The Divine Comedy, nor that his fascination with Dante has spanned his entire life. Similarly, there is a vast amount of his poetical work, and even essays, in which I have not indulged. I’m rectifying this one volume at a time.

So, it might be odd to consider James a keystone author in my life.

This is true if by influence you take it to mean insane fan. Yes, I’m a fan, albeit one with a growing appreciation for the breadth of the author’s talent and application. But the influence is in both Clive James’s style and in his knowledge of, application in, and handling of his critical works. And, necessarily, in his tone. Few essayists can combine a sharp tongue with a fine sense of humour, as Clive James does.

Clive James has been somewhat of a gateway drug for me in terms of reference to other literary critics. If you grew up knowing Clive James as that man who was on the telly talking about films, then the depth of his critical knowledge is something you’ve totally missed. Interestingly, the lessons of critique that have been most valuable to me have come from Clive James (a poet and essayist); Eugenio Montale (a poet and essayist); and those I’ve had the joy of learning from directly (among them, Myk Mykyta).

Poets, all. Essayists, all. Purveyors of literary criticism, certainly, but not necessarily academically. The academy is in the texture of their histories, not necessarily the meat of their daily lives.

In Kerry O’Brien’s interview with Clive James, James happened to mention that great works demand time. That poetry takes time, that essays take time. That it might take you an hour to craft a mere paragraph if you’re going to get it right. Or longer, perhaps. And that your mind will distract you in all ways possible. He mentioned that he’s difficult to live with because as a writer you need to follow your muse. Which might mean rising at 3 am to chase the sparkle as it occurs to you, or not sleeping until extraordinarily late. Or otherwise interrupting whatever others consider ‘normal’ life to be.

This sense of time is why his work is so well formed. By my side is one of his works, The Meaning of Recognition, which is a collection of essays. As an essayist, Clive James is undeniably luxurious to read. And one of the reasons is because he took his time. The time he took is woven into his prose; it is filled with space in which to think. Much of this clear-headed thought is supported by a clear and powerful vocabulary, wielded with both precision and delicacy.

In the interview with Kerry O’Brien, I winced in recognition when he pretty well said that you’re a dickhead if you write in a flurry and let it all go. That you are doing people a disservice by writing and releasing all in a rush. To me, this was an indication that if you’re going to benefit anybody by the works that you write, you have to respect them enough to take the time to do it well.

He’s right. In fact, I school writers myself to write, and let it sit, and review, and think, and work, and then release.

But in practice? I bash these blogs out with barely a second thought. Clive James, mentor at a distance, gave me pause. It is not conducive to good work to release it quickly, of that I know well. In my professional life, I never write and release. Everything sits for at least 24 hours. But here?

Well, maybe that will change. Time itself teaches us that rushing is not important. Doing is, certainly. But rushing, never.

The fact that Clive James takes his time is something which all essayists who wish to be taken seriously need to take note. He’s a poet. And like all poets, he is careful about the shape and song of his work. It is why Clive James’s essays also have a beauty in their shape, and tone and style. As he writes about other writers, examines television, pores over film, it made me realise that there are few in the world with the talent, experience, and skill as a critic as this man.

Who, when it is all said and done – knowing that he is ailing fast – is going to give Clive James the remarkable service that he’s done for so many others? How many critics and essayists are there who can run a fine-toothed-comb over his work, and sensitively assess both his shining ability and his cracks of failure, while all the time weaving in the sociopolitical influences of time, space, and place? And how many of those who are capable will give him the time?

Because when it’s all said and done, that’s the greatest service you could do for a writer like Clive James. Give him time. Read him slowly. Evaluate his works with at least half the consideration with which they were written.

It is unfortunate that in this day and age, when we’re besotted with speeding information flows, and reducing our collective capacities to think, that this is one luxury that Clive James may never be afforded.

Hi.

I only now found your reflections on Clive James. If you enjoyed Kerry O’Brien’s interview with Clive James, check out Jon Snow (Channel 4, UK) interview – even better, I think: https://www.channel4.com/news/clive-james-jon-snow-television-dante-video.

James’s Divine Comedy translation is a breakthrough in many ways. For critical commentary see for instance:

David Hart “Dante Un-cluttered” https://www.firstthings.com/article/2013/11/dante-decluttered

Also useful is Arabella Milbank’s “Review” of the translation here: https://www.firstthings.com/article/2013/11/dante-decluttered.

For critique (from an establishment figure) – the ‘dantisti’ so-called – see Ian Thompson blog entry: “Why Clive James’s translation is rubbish” here; http://www.ianthomson.info/blog/why-clive-jamess-translation-of-dante-is-rubbish/

Clive has use poetic license (a no-no for purists) but it actually finally delivers in English that delivers an impact closer to Dante original innovation of writing in the colloquial (vernacular) form. Being Italian, (and living in Sydney) I can see how The Divine Comedy works in both languages.

If you have the time …… give the translation a go! (Available on Kindle).

Hi Richard,

Thank you for your extensive comment and resources. I really appreciate you!

I have actually read most of my way through the translation since writing this, but haven’t yet finished it. I’m going to go and immerse myself in all of these links and thoroughly enjoy myself.

I’m grateful for you to have taken the time to add so richly to my post. 🙂

cheers

Leticia