I watched her for a while, before I knew she was me.

She was a woman of average height. She walked through a big, old building that had ceilings at a great height, ceilings curved like the inside of a Viking boat. Windows covered the eastern wall; a greyness beyond the glass, partly from years of neglect, partly because the light was grey. A swathe of brown-robed ghosted swooshed along in front of the window, easily mistaken for curtains billowing in the wind.

The woman I watched was walking between the worlds. She was here to learn the story of the sisterhood, the nuns that kept these halls in times gone by. They slept in dormitories that came off the long hallways to each side, each warmly-lit room filled to capacity.

Not all the women here were nuns. Many were isolated, alone, pregnant. This woman knew that there had been deaths here; the women who had died haunted the building, yet when she walked these halls there were fewer ghosts than when I first laid eyes upon it.

This woman was universally loved.

As she opened doors, laughter and light spilled out into the dull hallway. The warm, pink-and-yellow light from lamps, candles, and firelight brightened everyone’s day. The woman’s eyes lit up as she spoke, hugged, moved past again. She seemed to be universally loved.

It was when she was walking through these rooms that I learned that there was a group of women in these very halls who were due to give birth. They had been waiting for this woman to arrive. A breathless young lady told her that they’d been waiting too long, that they must all be delivered as soon as possible if things were to go well.

The woman agreed. Bring them forth, agreed.

They went well.

Except for one. One poor woman whom, clutching at her abdomen and screaming as though she were rent from within, collapsed and began to bleed profusely. The attending nurse didn’t realise that her child had shattered into a threaded cluster of sharp noodles, had torn holes in her uterus, ripping into her insides.

The screams echoed through the halls.

The woman was standing at the fire pit in the centre hall of the building. A young man, tall, handsome was to her left, at the northern point. An old crone across from her caught her eye in the firelight.

And suddenly I was the young woman in charge of this place, these women, these decisions. The young man was my son.

A young woman reported to me that two more women and there children had died.

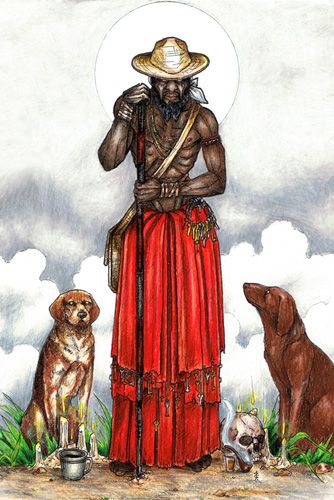

The bleeding woman wasn’t dead, but she would be unless we/she took steps to rescue her. Nodding to the young man who was my son, he pulled out a small, palm-sized book, cover-less, yellowed with age, edges torn, pages ink-stained. He began to read an invocation that was also a prophecy. As he read, blood stained the paper and spread through the pages. He brought Papa Legba and his loa into the place to resurrect the woman. The document became more and more bloodsoaked as the line between the worlds thinned.

As if I were the footpath, I saw bare feet stamp their way past me in a rush, themselves in yet another world somewhere beyond. Men’s feet.

I knew that in reading this book, my son would be taken in exchange for the dying woman. The crone, my son and I looked at each other, and each of us understood the implications.

It was prophesied.

It had to be this way.

But it was the end.

It makes a good story, doesn’t it? The foregoing is a dream that I woke up from, just before dawn on 1 May 2019, which is Samhain in Australia: The time when the veil between the worlds is its thinnest; when the old year dovetails into the new year; when old things die and new things begin. It fascinated me that Papa Legba was called forth in this dream; it’s the first dream in which he’s been called by name. I suspect that he’s appeared to me previously in dreams, in different guises; once in his famed top-hat.